The Clever Girl

The Clever Girl An Eastern European Tale

The Clever Girl

The Clever Girl

An Eastern European Tale

Once

upon a time there lived a poor farmer who had one—one and only—trusted treasure.

This was his daughter, Hannah.

One day

the farmer the farmers cows wandered into his neighbor's field, and as he was

herding them home, his neighbor stopped him. "That cow is mine," he said, pointing

at the last creature waddling through the gate."

"Oh no,

he's mine," the farmer said, and they went on this way for quite some time.

When at

long last they couldn't solve their argument, the farmer said, "Let us go to

see the magistrate. He'll judge this matter."

And so the

men set off to the palace to seek the magistrate's help.

Now the

magistrate was a kind man, but he was young and inexperienced. He listened

closely to the farmer.

"It must

be my cow. It followed the rest of the herd."

And then

he listened to the neighbor. "I know my cows. I recognize each and every one,

and I know it's MY cow."

The magistrate

shook his head, for he did not know what else to do, and after thinking a long

while he said, "I won't decide this case."

"But you must," the neighbor began.

"No," the magistrate said, "instead I shall give you a riddle and whoever answers

best shall win. Agreed?"

The farmer said, "Agreed," and the neighbor nodded. Both men were certain they

could easily answer a riddle.

So the magistrate said, "Answer me this. What is the swiftest thing in the

world? And what is the sweetest thing? And what is the richest? Return tomorrow

to tell me your answers and this case will be closed."

So the two men walked home.

The neighbor asked his wife to help him solve the riddle, and as she scooped

porridge into their bowls, she listened to the magistrate's question. Then

she smiled.

"That's easy," she said. "Our gray mare is the swiftest thing in the world.

No one ever passes us on the road."

"That's true," the neighbor said. "And the sweetest?"

"Easier still," said his wife. "That is our honey."

"Of course," the neighbor said, "but dear wife, what is the richest thing in

the world."

His wife laughed. "Why nothing can be richer than our chest full of gold we've

saved these many years, husband."

"Of course!" said the neighbor, pleased to have solved the riddle.

Meanwhile the farmer returned home, and when he told his daughter of the magistrate's

riddle, she sat down beside him and gently touched his hand.

"Father," she said, "please let me help you solve this."

You see, Hannah wished for nothing more than her father's happiness, and when

he told her the three questions, she smiled.

"Ah, easy," she said, and she gave the farmer the answers to solve the riddle.

The next day the two men returned to the palace, bowed to the magistrate and

the neighbor stepped forward. "I know the answers," he said, and he gave them

to the magistrate—"my gray mare, my honey, and my chest of gold," he said.

Then he grinned, confident he had won.

Then the farmer stepped forward. "I humbly answer, sir," he said. "The swiftest

thing in the world is thought, for thought can run the distance in the twinkling

of an eye."

The magistrate stared in wonder at the farmer. What a wise man.

"And the sweetest thing," said the farmer, "is

sleep, for when one is tired, nothing is sweeter."

The magistrate smiled. Wise man indeed.

"And the richest thing, sir, is this earth, for it is earth

that provides us with all our riches."

The magistrate was impressed by the farmer, for each response

had called for cleverness and thought. "Tell me, good man, how did you

come up with these answers?"

"Truth is," the farmer said shyly, "my daughter

Hannah gave these to me."

Now the magistrate thought for a long while, and then he said, "I

wish to make another test of your daughter's cleverness. Wait a moment."

The magistrate walked into the other room, and a few moments later, when he

returned, he held a basket.

"Take this basket of eggs to Hannah," said the magistrate. "Tell

her to have them hatched by tomorrow. All ten!"

The farmer raced home as fast as he could, and he handed the basket to Hannah.

He was panicked, for he could not imagine how his daughter could perform such

a trick.

But when

Hannah heard the magistrate's request, she laughed. "Father," she said calmly,

"take a handful of millet and return at once to the magistrate. Tell him

your daughter sends him this millet and if he will plant, grow and harvest

it by tomorrow, she will bring him ten chicks."

And so the

farmer raced back to the palace, and when the magistrate heard Hannah's answers,

he laughed heartily. "Clever girl, your Hannah. I would like to meet her."

"Certainly,"

the farmer said, but the magistrate held up his hand.

"But I have

one more test for her," he said. "Tell Hannah that she must come

to me, but she must come neither by day nor by night. And she must come neither

riding nor walking. And she must come neither dressed nor undressed. Tell her

that."

And so once

more the farmer raced home to tell his daughter of the magistrate's request.

"How on earth will you do this, dear daughter?" the farmer said,

for now the original argument seemed silly, and he wished he did not have to

trouble her.

But Hannah

embraced her father. "Do not worry, father. All's well."

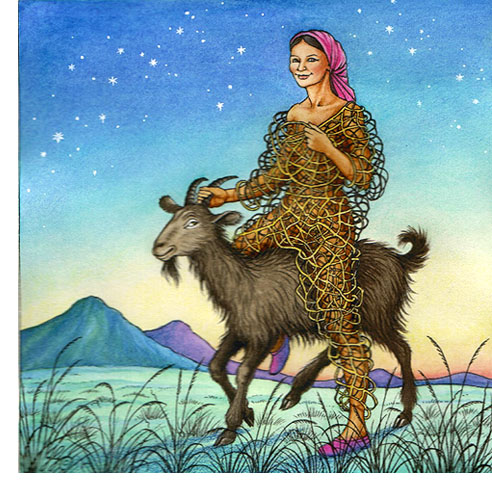

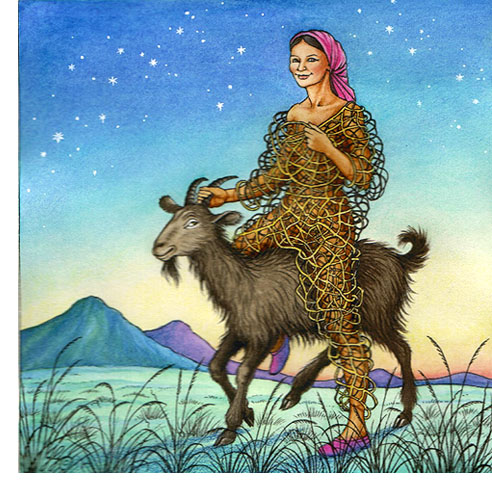

She waited

until dawn, the moment when night is well past and day has not yet begun. Then

she wrapped herself in fish netting, threw one leg over the back of a goat

and the other she kept on the ground. And in this way she traveled to the palace

to see the magistrate.

When she

arrived at the gate, she called out, "Sir, I am here. And as you demanded,

it is neither night nor day. I am neither riding nor walking. I am neither

dressed nor undressed."

Standing

at the window watching her, the magistrate was so taken with Hannah's cleverness

and so pleased with her wit, he fell in love. He walked to meet her, and he

bent down on his knee and proposed marriage to her.

In turn

Hannah was taken with the magistrate's wisdom, and with his wit, and with his

good nature, and so she accepted his proposal.

On the evening

of their wedding day the magistrate took his new wife's hands in his. "Hannah,"

he said, "you must understand one vital thing."

"What's that, dear husband," Hannah said.

"You must not interfere with my cases."

"What do you mean, my dear?" she asked.

"I love your cleverness, but if you ever use it to advise

someone who comes seeking my judgment, I will send you back home to your father."

"I promise, husband," Hannah said. "And I ask

you one promise in return."

"Of course," the magistrate said.

"If you ever choose to send me away, you will allow me to

take one thing from this house that I most treasure."

"Of course," the magistrate promised, for he was not

a greedy man.

And for a long time, Hannah and her husband lived happily together.

Then one

day two farmers appeared at the magistrate's court hoping he would settle a

dispute.

The first

farmer owned a mare that had foaled in the marketplace. Just after the mare

gave birth, the colt ran beneath the wagon of the second farmer.

Now the

second farmer claimed the colt was his.

The magistrate

was busy with other matters, and he wasn't listening closely as the men told

their tales, and when they had finished, the magistrate cleared his throat

and said, carelessly, "I judge the man who found the colt under his wagon

to be the true owner."

Now Hannah

overheard this judgment, and she was terribly upset with her husband, so as

the owner of the mare was leaving, she ran outside and tapped his shoulder.

"Sir," she whispered, "I beg you to return this afternoon. When

you come, bring along some fishing net. Stretch this net across the road outside

the garden gate."

The farmer

listened intently, for he had heard the magistrate's wife was a wise and good

woman.

"I will,"

he said.

"When

the magistrate sees you, he will ask how you expect to catch any fish in the

middle of a dusty road, and you must tell him it is just as easy to catch fish

in a road as it is for a wagon to foal."

"Ah," said

the farmer," and in this way the magistrate will see the injustice of

his decision."

"Exactly,"

said Hannah.

And that

afternoon the farmer did exactly as Hannah had told him. He stretched his fishing

net across the road, and sure enough when the magistrate saw this he shouted,

"What sort of foolishness is this? How do you expect to catch a fish in

the middle of a road?"

And when

the magistrate heard the farmer's answer, he frowned. "I understand," he said.

"My decision was wrong, and of course the colt belongs to you, sir, for

you were the owner of the mare."

The farmer

danced with joy. "Ah, thank you sir, and sir, your wife is a fine, fine

woman!"

Now the

magistrate understood. He ran to find Hannah, and he looked sternly at her.

"You have broken your promise to me, Hannah." He was terribly upset, but a

promise is a promise, and so he said, "Home you must go to your father,

this very day."

Hannah looked

steadily at her husband. "You are right," she said sadly, "but

do me one favor. We have been happy together; let us share one last supper

together. I wish us to part as friends."

The magistrate

could not say no, for he truly loved Hannah, and that night they sat down together

to share one last meal.

The magistrate

was delighted at the spread before him, for there stood each of his favorite

dishes. He ate and ate until, at last, he could not eat another bite. So full

he could not move, he fell fast asleep in his chair.

Hannah quickly

rose from the table, and without waking her husband, she instructed one of

the servants to carry him out to her carriage.

The next

morning when the magistrate opened his eyes, he saw to his amazement that he

was lying in a bed in Hannah's father's cottage.

"What's

this?" he roared, and then he looked up and saw Hannah smiling at him.

"Dear husband,"

she said gently, "you told me I might take the one thing I liked best

in your house. I took you, for it is you I most treasure."

The magistrate

could not help himself. He burst out laughing. Once again Hannah had outwitted

him. "I have been a fool, Hannah," he said, through tears of joy, "please

come home with me. You are my treasure."

He climbed out of that bed, got down on his knees, and he begged his beloved wife's forgiveness, and after that, whenever he had to make a difficult decision, he announced to one and all, "We shall consult my wife on this, for she is a most clever woman."